An Excerpt from active measures: part ii

PROLOGUE

First, the rockets. He saw the flashes off to the northeast, just before the horizon. Fired behind a hill six kilometers from the observation post, the salvo arced through the clear afternoon sky to his right, hundreds of exhaust plumes racing over the desert plain before him. Then came the rolling screech of their reports. The cleric beside him cringed at the noise, a robed wad of graying flesh too far from the seminary.

“Heard that sound before, baradar?” Taghavi asked solicitously.

“Many times,” replied Hojjatoleslam Ali Movahedi Hajisadeghi, adjusting the white turban around his head. “I commanded a Basij battalion in Abadan when Saddam sent his dogs into Khuzestan… Not a happy memory.”

Taghavi nodded curtly as the barrage continued. The hojjatoleslam was the supreme leader’s representative in the Revolutionary Guards, a man renowned for his bellicose sermons calling for war against the Zionists at Friday prayers in Tehran. He ought to be the last to shrink at the sight of what war truly was.

“Foolish, of course,” the cleric offered after a moment. “Forgive me, General.”

“Oh, but those dogs are all around us...” Taghavi looked back at the host of Iraqis on the observation post with them—great men, captains, and lords—distinguished men who scarcely a decade earlier either served Saddam or feared him. “Only now, we hold the leash.”

The salvo struck their targets atop a ridge to the northwest, swallowing the barren summit in a billowing cloud of smoke and flying dirt. “Allahu akbar! Allahu akbar!” cried some junior militia commanders in the crowd behind Taghavi. To his left, a radio crackled on the belt of Major General Thamir Mohammed Ismail.

“You may commence,” Ismail ordered over his circuit.

Taghavi lifted a pair of binoculars to his eyes.

Next, the guns. The crashing thud of the 125-millimeter shells pounded his chest. Then, the T-72 main battle tanks emerged from behind another hill two kilometers northeast of the observation post like a nightmarish wall of armored steel and dust, long cannons belching flame as they glided toward the ridge across the sandy, rolling ground of the exercise area. M113 armored personnel carriers (APCs) interspersed with the tanks charged forward as well, their movements closely coordinated. The Grad rockets kept up their barrage from afar and another salvo fell like hail on the ridgetop, pummeling the mockup bunkers and armored vehicles.

“Allahu akbar! Allahu akbar!” the cries behind him grew. “Glory to Imam Husayn!”

Taghavi carefully evaluated the exercise through his binoculars. It would be an awful day for anyone atop that ridge. Even sheltered in a fortified trench or a defiladed APC, the constant shower of exploding ordnance would leave any seasoned soldier terrified and concussed. Perhaps, Taghavi thought. But that was the problem with exercises. The enemy never shot back. What if the enemy could return artillery fire? What if the enemy had anti-tank weapons and air support? In all but a few scenarios Taghavi imagined, the enemy had all those things and more. What if it were Kurds atop that ridge? What if it were Americans?

Still, Taghavi had every reason to be proud. Major General Ismail and his deputy, Nayouf, the Alawite, had outdone themselves. The exercise was meant to simulate a coordinated frontal assault of tanks and mounted infantry against a force of equal strength. Forty HM-20 and HM-27 multiple rocket launchers and a howitzer battery provided fire support. A year ago, this level of coordination would have been impossible. A year ago, the sight down there would have been a circus. A year ago, Daesh—the Islamic State—still held Mosul, and Taghavi would have given anything to throw this storm at them. But there would be new enemies soon enough.

It took sixteen minutes for the tanks and APCs to reach their objective atop the ridge. The summit was a smoking ruin, and the plain below was a lacerated wasteland of tread marks. Ismail grabbed his radio and halted the exercise. The audience assembled on the observation post was all smiles and handshakes, some militia commanders exalting the name of God again or snapping pictures of the tanks still rumbling around the plain.

“Well done, General,” Taghavi called to Ismail over the dull ringing in his ears and offered his hand.

“It would not have been possible without your guidance, sayyidi,” he replied. “I pray that—” Celebratory Kalashnikov fire broke out in the crowd. “I pray that my men have earned the honor of their namesake.”

“Surely, the ayatollah is looking down from Paradise and could not be more delighted with the soldiers of the Imam Khomeini Division.”

Major General Ismail was too reputable for this rabble, Taghavi sometimes thought. Ismail was a decorated veteran of the Battle of Mosul, perhaps the most distinguished Shiite in the Iraqi officer corps. He led the Interior Ministry’s American-trained-and-equipped Wolf Brigade until Taghavi’s associates recruited him to command the Imam Khomeini Division. That a man of Ismail’s caliber now served Taghavi and, by extension, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), was its own insult to the Americans.

The rest of the delegation visiting from Tehran began to approach, all eager to get their piece of Ismail.

“General, you are too young to remember Imam Khomeini,” Hajisadeghi said, pulling the rubber plugs from his ears, “but to have such a mighty force bear the name of the leader of the Islamic Revolution is the finest memorial to his legacy.”

The cleric cannot utter a word without preaching hyperbole, Taghavi thought.

“The hojjatoleslam is too kind,” Ismail nodded politely. “Will you tell His Excellency that it is a shame he could not be with us today?”

“I will. Inshallah, the supreme leader’s health will improve, and he can witness the next exercise himself.”

Taghavi turned and smiled at the other Pasdaran officers. “Baradars! Please, join us.”

Brigadier General Yahya Zolghadr, chief of the IRGC Joint Staff, embraced Ismail and planted a kiss on either cheek. “If I recall, General, the Syrians completed this exercise in twenty minutes. Your timing was...? Seventeen?”

“Sixteen minutes and twenty-three seconds,” Ismail answered proudly.

“Outstanding, General. Just outstanding.”

“The tanks and troop carriers cooperated well,” Rear Admiral Ali-Akhbar Ahmadian, director of the IRGC Strategic Studies Center, said from the edge of their circle. “I’ve never seen the use of rocket artillery integrated so closely, but that, too, was impressive.” Doctrinally, the Imam Khomeini Division was Admiral Ahmadian’s brainchild, albeit birthed by Qasem Shateri’s sheer force of will.

“In my view, the greatest improvement was the coordination of artillery fire and infantry in the final assault phase—a tricky procedure,” added Brigadier General Hossein Pakpour, deputy commander of the IRGC Ground Forces.

“Before, they failed miserably. We’ve drilled for months to achieve that level of cohesion,” Ismail admitted frankly. “Brigadier General Nayouf applied the lessons from Homs and Idlib. The credit is his.”

“Then we must toast him later,” Zolghadr nodded.

A line of SUVs and technicals with heavy machine and anti-aircraft guns mounted to their beds pulled atop the hill. At least two dozen mujahideen poured from the convoy, all cheering and searching the crowd for their comrades. Taghavi saw the flags over the vehicles flapping in the breeze. Many bore an AK-47 superimposed over a globe and a map of Iraq against a green field with the Quranic verse, “And already had Allah given you victory at Badr.” Others featured variations of a raised fist clenched around a Kalashnikov punching forth from the silhouette of Iraq over different verses in Arabic calligraphy. Taghavi knew them well: “And strive in His cause as ye sought to strive. He has chosen you,” and, “They were youths who believed in their Lord,” or, “And those who strive for us—we will surely guide them to our ways.” Spread among them was a yellow standard centered on a roundel carrying the red, white, and black stripes of the Iraqi flag bearing the title, “al-Hashd ash-Shaabi,” or Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), the umbrella under which that vast host of militias operated.

Just then, a booming voice pierced the cheers and scattered rifle fire. “Mohandis!”

Taghavi turned and saw a stout, middle-aged man walking toward him through the crowd, eyes hidden behind aviator Ray-Bans. The man had a round, hardened face and cropped gray beard and wore a khaki field shirt, cargo pants, baseball cap, and combat boots. It was Haider Mohammed Hatem, secretary-general of the Badr Organization, the PMF’s largest militia. He was flanked by three of his senior brigade commanders and Hamid Malik al-Amerli, chief of staff of the PMF.

“Abu Mahdi al-Mohandis!” he called again, using the nom de guerre given to Taghavi long ago by Iraq’s Shia revolutionaries.

“Haider!” Taghavi called back.

“What a day! What a day!” They embraced, kissed cheeks, and then Hatem warmly greeted the other Iranians and Ismail. “Beautiful work, son. Beautiful!” Hatem squeezed Ismail’s hands so hard, Taghavi briefly thought he might crush them. “Look at it!” he gestured theatrically at the ridge. Smoke hung low over the summit, distant fires still raging around targets.

“A wondrous sight,” Ismail said humbly.

Hatem took a deep breath. “That smell...” He shook his head and exhaled. “I would divorce both of my wives for a chance to chain some Daesh sister-fuckers inside those bunkers.”

The Iranians laughed at that. But not Taghavi.

“What’s stopping you?” Zolghadr chuckled.

“The angry call our friend would receive from Haj Qasem for using prisoners as target practice,” Taghavi answered coldly.

Hatem grunted and pressed his hands to his wide hips.

Al-Amerli, a small, rat-faced man with a weak chin, stepped from Hatem’s shadow. “Perhaps Haj Qasem should allow some early bloodshed,” he suggested casually, nodding to the burning ridge. “Soon, that will be Erbil’s fate, and Kurds feeding the flames.”

Minutes later, Taghavi was in the back of an armored Lexus LX at the center of a motorcade that stretched nearly a mile, roaring south down Highway 3 out of the Jallam Desert in Diyala province. The motorcade was a riotous parade carrying over two hundred armed mujahideen. Flags of every militia whipped violently against the dusty wind. Subwoofers and coaxial speakers mounted in some vehicles blared tinny martial songs extolling the magnificence of Hashd Shaabi’s sacred victory over Daesh and the bravery of its martyrs. SUVs, Humvees, and technicals weaved in and out of loose formations across either side of the highway, men cracking jokes to each other from open windows and sunroofs. Outriders sent ahead forced passing traffic onto the shoulders. When the motorcade came hurtling by, whole families were out of their cars, children sitting on their fathers’ shoulders, clapping and cheering, praising God for the saviors of Iraq. A Toyota Hilux pulled alongside Taghavi’s Lexus and matched their speed. The driver rolled down the window, reached out and held up his thumb, smiling from ear to ear. In the truck’s bed, a pair of Saraya al-Khorasani fighters seated around a Browning .50 caliber machine gun spotted Taghavi behind the two-inch-thick polycarbonate window and went wild.

“Mohandis!” they shouted gleefully. “Mohandis!”

Sitting to his left, Taghavi’s chief of operations, Colonel Shahroud Mozaffari, gave a slight eye roll. “These Iraqi boys think you’re some movie star.”

“To them, you are, baradar. You’re their icon,” Captain Vahid Zamanian, Taghavi’s aide-de-camp, said earnestly from the front passenger seat as the Hilux started honking. “These men stared down death and won because you gave them faith to confront it. They placed that faith in you.”

Taghavi nodded shyly and waved. “They’re just teenagers...”

“And there are martyrs much younger,” replied Zamanian.

“Mohandis! Mohandis! Takbir!” the boys cried over the horn.

He pressed the button to bring his window down, but the armoring let it drop only six inches.

“Quickly, sayyidi,” his Iraqi driver and bodyguard, Mohammad al-Sabih, said sternly. “Quickly.”

Taghavi reached through the gap and made a V sign with his fingers. “Alhamdulillah!” he called to them, although he doubted they could hear him over the wind and the engines.

But the boys were ecstatic. “Mohandis! Alhamdulillah! Mohandis! Labaik ya Husayn!”

“Salam! God bless you!” he said, then rolled the window back up. The boys cheered once more and sped toward the head of the motorcade.

Taghavi grinned. There was always a fuss wherever he traveled in the country—an occupational hazard, albeit a welcome one. Camp Husayn tonight would be no different.

Brigadier General Jamal Jafaar Taghavi was commander of the Ramazan Corps of the IRGC’s Quds Force, Qasem Shateri’s “viceroy” for Iraq. The Quds Force was the expeditionary paramilitary, intelligence, and special operations arm of the Revolutionary Guards, charged with liberating Muslim lands, Jerusalem most of all—the holy city from which the force took its name, al-Qods in Arabic. Since 1979, the Quds Force had exported Imam Khomeini’s Islamic Revolution across the Middle East and beyond. In Lebanon, its officers molded Hezbollah into a professional military and social organization vastly more powerful than the national government. In Gaza and Palestine, the Quds Force advised and equipped Hamas and Islamic Jihad in their insurgency against Israel. Amongst the dispossessed Shiites of Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Kuwait, operatives organized covert cells that could wreak havoc against their Sunni dynasties with a simple order from Tehran. In Afghanistan and Pakistan, the Quds Force recruited over ten thousand tribal Shias and ethnic Hazaras into two foreign legions that butchered scores of jihadists on Syrian battlefields. In Yemen, Iranian officers trained and funded the Shiite Houthi movement in a bloody struggle against an international coalition backed by the Saudis and Emiratis. But it was in Iraq where al-Qods found its greatest success, Taghavi would claim. Hezbollah be damned.

Iranian involvement in Iraq reached back to the early 1980s. At the time, Taghavi was a chemical engineering student at the University of Basra, the son of an Iranian father and an Iraqi mother, and a member of the outlawed Dawa Party. Abandoning his studies, he fled across the Shatt al-Arab to Ahvaz, where the Quds Force had established a camp to train Iraqi Shias to undermine Saddam Hussein’s regime, founding the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI) and its military wing, the Badr Corps. Taghavi joined the Quds Force in 1983, claimed Iranian citizenship and an Iranian wife, and deployed to Kuwait to plot attacks against embassies of countries that supported Saddam in the Iran-Iraq War, where he met Qasem Shateri. For his role in bombing the US and French embassies in Kuwait, he was sentenced to death in absentia and remained in Iran until, finally, the Americans did what untold thousands of martyred Iranians could not and overthrew Saddam.

Taghavi returned to Baghdad in the summer of 2003, armed with orders from Qasem Shateri to hijack the nascent government, turn the country into an Iranian client and make the Americans bleed so long as they remained on Iraqi soil. Taghavi picked up the threads he’d left behind long ago—the Badr Corps and his old comrades from Dawa, tribal gangs from Sadr City, and criminal syndicates from his hometown of Basra—and began sowing together a web of Shia militias that would grow through the American occupation, through the sectarian butchery of the late 2000s, and through the Islamic State’s rampage into what was now the Popular Mobilization Forces, a quasi-state-sponsored confederation of some forty factions fielding 150,000 men-at-arms, arguably the most battle-tested fighting force in the Middle East, all of them sworn to uphold the authority of Ayatollah Ali Mostafa Khansari, and all of them placed under Taghavi’s command.

The Imam Khomeini Division was the natural culmination of the Quds Force’s mission to export the Islamic Revolution, a science perfected by Taghavi and his associates over years of trial and error on the battlefields of Saladin and al-Anbar and Nineveh. The division began in a white paper published by Rear Admiral Ahmadian’s Strategic Studies Center. The white paper analyzed lessons learned from the disastrous outcome of the Syrian civil war and proposed that the Quds Force might bolster their efforts to forge Hashd Shaabi into a professional military force on equal footing with (or far surpassing) the Iraqi Armed Forces by raising a unit of elite shock troops recruited from the ranks of all militias, avoiding the factionalism that plagued Iranian-backed groups in Syria and delayed the PMF’s initial response to Daesh’s uprising from within the Sunni tribes. Shateri eagerly latched on to the idea, attracted by the opportunity to essentially create a republican guard directly under the Quds Force’s operational control and away from individual militia commanders who may grow to harbor conflicting loyalties and ideologies. Taghavi was assigned the task of building this unit.

Their model was the Syrian Army’s 4th Armoured Division, a Damascus-based formation once commanded by President Hafez Jadid’s brother, which, along with the Republican Guard and the mukhabarat, comprised the backbone of the regime’s security services. Membership in the 4th Armoured was drawn almost exclusively from Alawite families, and nearly ninety percent were career soldiers, not hastily trained conscripts like most Syrian Army units. Command over this ambitious experiment was given to the irreproachable Major General Ismail, poached away from the Interior Ministry by Haider Mohammed Hatem, while Ismail’s deputy was to be Brigadier General Rukin Nayouf, himself a Syrian Alawite and a former 4th Armoured brigade commander who escaped the regime’s collapse.

The new division was built around three armored brigades, two mechanized brigades, one artillery regiment, one special forces regiment, and came to number twenty thousand strong. While the fighters were supposed to represent all PMF militias, Shateri approached recruitment more strategically. Men were disproportionately plucked from Baghdad neighborhoods dominated by the most loyal commanders: Palestine Street, Sadr City, Karrada, and al-Jadriya. The true purpose of the Imam Khomeini Division, as Taghavi understood, was to seize Baghdad and the national government without firing a shot, if ever that order came. The rationale was that police and security forces in the city would never dare fire upon a crack division of twenty thousand local Baghdadis marching on the Green Zone with tanks and APCs—childhood friends and neighbors, men whose families and fates were intertwined. Or at least, that was one of the division’s true purposes. The other, Shateri confided in Taghavi after prayers late one night, was to reduce Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, to cinders.

After years of planning and training, the Imam Khomeini Division was finally constituted and operational: battle-ready, as demonstrated on that ridge. Taghavi wished the division could have been activated in time to help defeat the Islamic State, but he didn’t dwell on that minor disappointment. The division was his crowning achievement after three decades of service to the Islamic Revolution, his answer to the arrogance and hubris of Hezbollah under Wissam Hamawi. Taghavi recently saw his sixty-second birthday—he had a few years on Haj Qasem—and knew his time in the field neared its end. Retreating to a comfortable office in Tehran was not his way. Thanks to him, the Quds Force’s mission was first realized in Iraq, not Lebanon, and that was more than enough for an old man’s pride. The Imam Khomeini Division would be his legacy. How that legacy was deployed—whether to capture Baghdad, burn Erbil, or languish in endless training exercises—was not his concern. Tonight, Taghavi would celebrate with his comrades and then reveal where their next battle would be fought.

“Sheikh Abd-Abbas will lead Maghrib prayers and give a sermon,” Captain Zamanian read from the evening’s itinerary, “then dinner with the men. After, they’ve set aside a few hours alone with the commanders to discuss the Mount Qandil situation, as you requested.”

Taghavi nodded. “And with whom did Haider pack the room?”

Zamanian cleared his throat. “Chairman al-Fayyad and al-Amerli. Then it’s just the principal commanders: the Khazalis—”

Colonel Mozaffari grunted in annoyance.

“—al-Saghir, al-Zaydi, al-Walai, al-Kaabi, and al-Asadi,” the captain continued.

Farther down Highway 3, the blunted corner of a twenty-foot earthen berm topped with loosely coiled concertina wire fixed to metal stakes emerged through the haze and dust like the windblown façade of an ancient ziggurat, running east toward the horizon in one direction and south following the highway in the other. The dashboard radio squawked a few words in guttural, Baghdad-accented Arabic. Al-Sabih replied, then announced, “Five minutes, sayyidi.”

The motorcade continued for several miles and then tightened its formation, merging into a single-file line as vehicles at the head turned left onto a paved access road that ran through a gap in the berm. The first of two checkpoints, seated comfortably in the gap, was a fortified hodgepodge of guard posts and HESCO gabions packed with sand and gravel. Al-Sabih veered sharply with the technicals providing close security to the Lexus and the other trailing armored SUVs. Uniformed Badr fighters raised the boom gates and waved them through—dozens of vehicles weaving between Jersey barriers at high speed, men honking and cheering as they passed. Beyond the berm, across five hundred meters of open desert, were staggered rows of steel hedgehogs large enough to shred the engine block and front axle of a careening, explosives-laden dump truck. Two twelve-foot defensive walls stood at the second checkpoint. The outer wall was made of anti-climb chain-link mesh crowned with more concertina wire. Seven meters back, the inner wall was constructed with modular T-shaped sections of steel-reinforced concrete bolstered by an additional row of gabions. Watchtowers rose every three hundred meters along the inner wall, each equipped with DShK heavy machine guns and 40-millimeter grenade launchers. Clearing the second checkpoint, Taghavi’s Lexus passed through the imposing, ornamental wrought iron gates of Camp Husayn.

The vast compound—sprawled across a fourteen-square-mile tract of desert forty kilometers north of Baghdad and eighty kilometers west of the Iranian border—was once known as Camp Ashraf, founded in the late 1980s as headquarters of the Mojahedin-e Khalq (MEK), or the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran. Taghavi despised the Monafiqeen, or “hypocrites,” as most Iranians called them. Terrorists, Marxists, and cultists, the MEK aligned with Saddam against the Islamic Revolution and bought access into the dregs of Washington foreign policy circles, presenting themselves as a “government in exile” that could take charge if the Americans overthrew the supreme leader. The idea was laughable. After Saddam’s overthrow, Taghavi orchestrated a string of assaults on Camp Ashraf and pressured Baghdad to evict the MEK. Eventually, two thousand Monafiqeen were driven out and forced to resettle in Albania. Camp Ashraf was left derelict and abandoned until the Badr Organization seized it as a base against the Islamic State. A spoil of war, the compound was renamed Camp Husayn for the third Shia Imam, martyred in 680 at the Battle of Karbala.

It was fitting, Taghavi thought, a symbol of how the IRGC and its Iraqi allies had decimated their enemies, the Islamic State and Monafiqeen alike.

Although now a major stronghold of the Badr Organization, Camp Husayn was the PMF’s primary training grounds, home to its Diyala Operations Command and garrisoned by forces from at least ten militias at any time. The camp operated on the scale of a modern town, with facilities to sustain thousands. It had a power station, a water filtration plant, three massive kitchens and mess halls, a hospital, a school, and two mosques. There were barracks, warehouses, and a motor pool. There was a firing range, obstacle courses, and a “kill house” where mujahideen could train in close-quarters combat exercises. On the northeast corner of the camp, rows of igloo-shaped munitions bunkers were built into artificial hills. In the wake of unmitigated victory, Camp Husayn demonstrated that al-Hashd ash-Shaabi was the dominant power in Iraq.

The motorcade dispersed once through the gates. Some sections broke off for the barracks or the motor pool while the bulk of the convoy followed the main road deeper into camp, slowed, and snaked onto an expansive parade ground where thousands of mujahideen were assembled on the fresh black pavement in three brigade-sized formations. Taghavi craned his neck to get a better look as al-Sabih steered the Lexus around.

“Did you know about all this?” he asked Mozaffari.

“I heard al-Fayyad was putting on a show.”

The Lexus stopped and Taghavi let himself out. Mozaffari and Zamanian were soon at his side. Al-Sabih moved around to him, quickly supported by the remainder of his protective detail—the Iraqis Hassan Hadi, Heydar Ali, and Mohammed al-Jaberi—from the nearest chase car. The rest of his delegation, Hojjatoleslam Hajisadeghi, General Pakpour, General Zolghadr, and Admiral Ahmadian, emerged from another SUV, as did Hatem, al-Amerli, and the others.

Awaiting him stood Dr. Faleh al-Fayyad and a host of Iraqi military officers, Shi’ite parliamentarians, and Baghdad technocrats. “Mohandis!” al-Fayyad said jovially, pecking him on either cheek. “As-salamu ‘alaykum.”

“Wa’alaykum as-salam,” Taghavi replied, careful to match the cheer in his tone—no more, no less. Al-Fayyad was five years younger than Taghavi and yet looked five older. White hair, jowls, eyes like a dead fish; Taghavi liked him no more than needed to suffer his company and trusted him no more than anyone bothered to trust him.

Faleh al-Fayyad was the chairman of the Popular Mobilization Forces and a security advisor to Prime Minister Nouri al-Rubaye. His role was to serve as a bridge between the militias and the government in Baghdad, maintaining the conceit that the PMF was a legitimate, quasi-state entity operating under sanction of the Iraqi Armed Forces. In reality, everyone understood that the PMF operated under no sanction but Haj Qasem’s. True power was exercised through Taghavi and a few principal militia commanders purely by virtue of their relationship with Shateri. Al-Fayyad had no such relationship, nor would he, and thus his role was little more than ceremonial. Whether he understood that or not, Taghavi couldn’t say.

“Doktor, I must introduce some friends who’ve seemed to follow me from Tehran,” Taghavi said with a smile, then went down the line with each Iranian officer.

After exhausting their pleasantries, Major General Ismail stepped forward and saluted. “General Taghavi. Brothers. Sayyids,” he said. “May I have the honor of presenting the fully constituted and operational Imam Khomeini Division?”

“You may, General,” Taghavi answered.

Ismail saluted again and turned sharply.

Taghavi turned as well, looking out across the parade ground. The delegation lined up beside him.

The sight filled Taghavi with pride. On his left stood vast ranks of men, all in mismatched desert camouflaged fatigues, some with bits of combat webbing and various gear, wielding Kalashnikovs, light machine guns, and RPGs. Held above them in the breeze were the banners of dozens of militias, large and small. Taghavi saw the standards of Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, Kata’ib Hezbollah, Saraya Ashura and Saraya al-Jihad, Kata’ib al-Imam Ali, Liwa Ali al-Akbar, Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba, Liwa al-Tafuf, Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada, Saraya al-Khorasani, Jaysh al-Mu’ammal, the Ninawa Guards, Kata’ib Jund al-Imam, and still more whose flags were obscured by those in front. To his right, the ranks were equally vast. The men’s fatigues were forest camouflage, a bright yellow silk scarf was tucked neatly between their shirt lapels, and each wore a baseball cap embossed with the symbol of the Badr Organization. Over them flapped the banners of Badr brigades 4, 20, 23, and 24 and the local auxiliaries Kata’ib Babiliyun and Liwa al-Turkmen. But the sight of the third and largest formation brought him nearly to tears.

Five thousand mujahideen stood before Taghavi.

Their uniform was black fatigues and a black baseball cap. All five thousand were armed with a Heckler & Koch G3A6, the standard-issue battle rifle of the Revolutionary Guards. Each man wore an emerald-green armband around his right sleeve. The standard flying above their ranks was uncanny to Taghavi, unlike any over the parade ground. He eyed the familiar four crescents and sword joined in the shape of a tulip, the emblem of the Islamic Republic of Iran, which was also embossed on their caps. Yet set against this emblem were the horizontal red, white, and black stripes of the Iraqi flag. Together, they formed the newly unfurled standard of the Imam Khomeini Division.

Ismail nodded to his deputy, Brigadier General Nayouf, who saluted in response, turned to the ranks, and bellowed, “At-ten-tion!”

At once, in perfect unison, all five thousand mujahideen snapped into a rigid posture, legs locked, heels together.

“Eyes front!”

Their eyes fixed on some distant point, faces blank.

“Pre-sent arms!”

They swiftly brought their H&K G3s around to the front of their bodies, the underside of each rifle facing outward.

“Order arms!”

The butts of five thousand rifles came down against the pavement with a metallic clack.

Nayouf turned and saluted to Ismail, who did the same and stepped forward.

“Victory is ours by the will of God!” Ismail boldly proclaimed. “Against Daesh, we have prevailed and defeated barbarism. We have proved again today that we can defend Iraq against its enemies. Alhamdulillah, we have cleared the earth of this vermin thanks to these valiant men,” Ismail pointed directly to Taghavi, “God’s grace, and the—”

“Mohandis!”

The cry came from Taghavi’s left, somewhere among the other militias. Then more followed...

“Mohandis! Mohandis!”

Those cries came from the right, amid Badr’s men. The next erupted from within the disciplined ranks of the Imam Khomeini Division. “Mohandis! Takbir!”

In an instant, his name was on all their lips. “Mohandis! Mohandis!”

Hatem leaned into Taghavi’s shoulder, a beaming smile across his face. “They love you, sayyidi!” he exclaimed against the roar of thousands of voices. The other officers and chieftains watched in stunned silence.

Taghavi had no words to describe the pride he felt then. He wiped a tear from his eye, listening as they chanted for him.

“MOHANDIS! MOHANDIS! MOHANDIS!”

• • •

The guest house sat atop a hill in the southern section of the camp. From the patio, clear as the night was, Taghavi looked out across the compound. Militias descended on Camp Husayn from as far as Tal Afar and Basra, and even a battalion of Afghan Shia Hazaras from Liwa Fatemiyoun had come to witness the birth of the Imam Khomeini Division. The barracks and mess halls were packed beyond capacity, and brigade commanders had ordered their men to pitch tents wherever they could find room. Now a hundred cookfires burned across the camp, and the distant sound of martial music mingled with thousands of disembodied voices. Taghavi had never seen it so alive.

It might have been a gorgeous night, but he and his lieutenants had unpleasant things to discuss. He sipped his chai from a tiny glass rimmed with gold leaf and stepped back into the sitting room through the open French doors.

Taghavi glanced at Zolghadr, then checked his watch. “It’s late.” He looked to Zamanian. “Baradar Vahid, my satchel.”

Zamanian nodded and went down the hallway.

“Friends,” he said, “let’s move this to the dining room.”

Once everyone squeezed inside, the guest house’s dining room felt nearly as crowded as the camp below. Taghavi stood at the head of the long Empire-style table; Brigadier General Yahya Zolghadr, chief of the IRGC Joint Staff, stood at the foot. Packed shoulder-to-shoulder around the table was the deputy commander of the IRGC Ground Forces, Brigadier General Hossein Pakpour; PMF chairman al-Fayyad and chief of staff Hamid Malik al-Amerli; Taghavi’s chief of operations, Colonel Mozaffari; and the commanders of the PMF’s seven largest militias: Haider Mohammed Hatem, secretary-general of the Badr Organization; Sheikh Jalal Ali al-Saghir of Kata’ib Hezbollah; Qais and Laith al-Khazali of Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq; Shibl al-Zaydi of Kata’ib al-Imam; Abu Ala al-Walai of Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada; Akram al-Kaabi of Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba; and Ahmed al-Asadi of Kata’ib Jund al-Imam. Captain Zamanian unfolded a map across the table. It detailed the northern half of Iraq, from Baghdad across three hundred miles to Turkey. The semi-autonomous Kurdish Regional Government’s line of control was marked in purple, running jaggedly from the Iranian border near Khanaqin in Diyala province and skirting the edge of Tuz Khormato, continuing around the oil fields south and west of Kirkuk—still occupied by Kurdish peshmerga forces a year after the threat from ISIS was eliminated—and farther north, encompassing Erbil and Sulemaniyah, then roughly following the Tigris River, looping around Mosul’s eastern suburbs at Bashiqah, and ending at the Yazidi village of Faysh Khabur on the Turkish border. Between Taghavi and Mozaffari, Zamanian set a thick folder.

Taghavi cleared his throat. “Some of this will be review. Some of this will be new.” He nodded for Mozaffari to begin.

The colonel removed a photograph from the folder and placed it on the table. It captured a towering beast of a man, rising six-foot-four with glimmering eyes and a long nose. His coarse jet-black hair fell in unruly curls down his neck like a mane, and his thick, full beard was tied with thread into three prongs. The man’s muscular arms were pressed to his waist, and he struck a triumphant pose amid a patch of purple thistles spattered with fresh blood.

“This is Major General Jamil Gorani, who until three months ago commanded Fermandayee Erbil, a regional command of the Kurdistan Democratic Party’s peshmerga forces in the capital...”

Laith al-Khazali smirked at his brother.

“A monster,” said Shibl al-Zaydi.

“A capable monster,” Hatem cut him off.

“During the war, Gorani was charged with defense of the plains between Mosul and Erbil. This photo was taken as Gorani’s forces repelled a Daesh assault on their position. Thus, the blood on the thistles, and his nickname: ‘The Dark Lion of Kurdistan,’” Mozaffari continued. “Gorani came under criticism by the KDP and Ezzedine Barzani for recruiting a personal militia among Christian, Yazidi, Sunni, and Shia fighters. Men, women, he did not discriminate. These fighters swore a personal oath to him. He called this militia his ‘sons.’”

“The Sons of Gorani,” added Taghavi.

“After Daesh’s defeat, Gorani became outspoken about the need for Kurds to turn their guns upon the Islamic Revolution and its mujahideen in Iraq. When it became clear Barzani could not rein him in, we decided to act.”

“This was supposed to be handled,” al-Fayyad grumbled.

Mozaffari looked to Hatem. “I managed the operation myself. To leave distance, we contracted a team of local assets in Basra through the usual channels, one used by Badr in the past. A week later, the assets struck Gorani’s home. His wife and eldest son were liquidated; the general was unharmed. Gorani blamed Haj Qasem, vowed revenge, and renounced his ties to the peshmerga. Three months ago, the general was spotted with his militia in the PJAK camp on Mount Qandil. He hasn’t been seen since.”

“Then he has been trapped in the mountains all winter,” Sheikh al-Saghir reasoned. “He’s found shelter among the terrorists.”

“He’s found shelter among the terrorists, yes,” Taghavi agreed, “but he’s not waited for the weather to turn, sayyidi.” Taghavi smoothed another map over the table. This one focused on the narrow, mountainous valleys and isolated villages peppering Iran’s northwestern border region in West and East Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, Kermanshah, and Ilam provinces.

He tapped on Mahabad in West Azerbaijan province.

“Seven weeks ago, a maid at a hotel in the city jumped from a window to her death. The claim is that an Intelligence Ministry officer raped the girl. There have been protests in Mahabad and general unrest in the provinces since.” Taghavi drew his finger south, closer to the border, and landed on Lake Zarivar. “Coming to the first event. Three days after the maid’s suicide, Khalid al-Talabawi, a Badr Organization logistics chief based here at Camp Husayn, you’re aware, was found murdered here beside the lake, near the Penjwin border crossing.”

“Professional,” Mozaffari added. “Three clean shots.”

Taghavi’s finger moved north. “Next, two lieutenants from the Pasdaran provincial corps in Piranshahr—Sahand Aslani and Nader Diba—were assassinated by a sniper outside a restaurant.” He looked up at General Pakpour. “Both had recently returned from Diyala.” He paused and took a breath. “The last two men, of course, we knew intimately.” Taghavi slid his finger south and touched Sanandaj. “Behrad Taghipour, assistant defense attaché at our consulate in Erbil, an officer of mine, was ambushed outside town along Highway 46. Small-arms fire raked his vehicle; he bled out before an ambulance could arrive.” Taghavi again tapped on Mahabad. “And then, three weeks ago, Major Ghafoor Kargari. My aide-de-camp. Two masked terrorists on a motorbike attached a bomb to his car door and sped away. The explosion killed Ghafoor and his driver. I was meant to be in that car with him, but my itinerary changed last minute.” Taghavi stood straight and folded his arms. He looked to Zamanian. “Baradar Vahid is here with us today because of this attack.” Their eyes all landed on the young captain. “But his predecessor won’t be the last to die.”

“These assassinations required impressive planning and tradecraft,” Mozaffari informed them. “They demonstrate an ability to maintain persistent surveillance on multiple targets on either side of the border.”

“The Zionists,” al-Fayyad said confidently. “Mossad.”

Mozaffari shook his head. “The concentration of targets in the border area over a short period would suggest it’s not. The Zionists are focused on Tehran, on more strategic targets.”

“You believe it’s Gorani?” offered Qais al-Khazali.

“After Taghipour’s assassination, Haj Qasem brought in the Etelaat-e-Sepah, the Pasdaran’s Intelligence Protection Organization, and others in the chief commander’s office,” Taghavi revealed. “They’ve pressed their sources inside Kurdish security forces and the separatist groups and learned a courier affiliated with Gorani has visited Mount Qandil on at least four occasions over the last three months and maintains contact with PJAK’s intelligence network on our side of the border, which we have not penetrated to the extent of Kurdish Asayish. We believe Gorani has a force of fifteen to twenty fighters and that sympathetic villagers are sheltering him near the border in West Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, or Kermanshah.”

“The Kurds are a cancer! No different than Daesh!” Laith al-Khazali spat on the floor. “They must be exterminated at the root. We must eradicate the virus. It’s the only way to save the rest of the body.”

“This is not a cancer, my friend,” Taghavi replied calmly. “This is a persistent stomach ulcer.”

“How do you mean to stop him, sayyidi?” asked Akram al-Kaabi. “A nuisance he may be, but he’s operated with impunity.”

Taghavi looked up with a slight grin. “We must purge the body together... Baradar Yahya?”

Brigadier General Zolghadr placed the larger map of northern Iraq on the table again. “On the advice of His Excellency Ayatollah Khansari, the Supreme National Security Council tasked the Pasdaran Joint Staff to formulate a response that addresses the unrest in the provinces and eliminates Jamil Gorani and any support network he may possess. We reached out to the Quds Force and the Ground Forces and, with their input, devised a multi-phase offensive operation into the Kurdish territories. Baradar Hossein will elaborate further.”

Brigadier General Pakpour maneuvered closer to the table and leaned over slightly, making his way around the map as he described the operation.

“On March 26th, four weeks from today, the Pasdaran will commence its annual spring Eghtedar-e Velayat exercise in the northwest,” Pakpour began. “Under cover of this exercise, the Ground Force’s Hamze Seyyed-al-Shohada Headquarters will assume operational command of five provincial corps from West and East Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, Kermanshah, and Ilam, mobilizing alongside Artesh cavalry and infantry units, fighter aircraft, and attack helicopters. This will be a 20,000-strong force surging into the border region. As PKK and PJAK separatists flee into the mountains, Saberin commandos will pursue them into Iraq while Mount Qandil is bombarded from the air. We estimate the sweep will be concluded in three weeks with minimal casualties—under two hundred, at most.”

Hatem’s eyes were glued to the map. “And what becomes of those separatists when they flee back to our side of the border?”

“You slaughter them,” Taghavi deadpanned.

“Leave their corpses to rot as feasts for dogs and birds,” Laith happily agreed.

Taghavi brought their attention far south, landing his finger on Khanaqin, a village in Diyala straddling the line of control between the Badr Organization and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan’s (PUK) peshmerga forces. “There’s a Feyli militia here in Khanaqin, yes?”

“Yes,” Hatem answered. “Brigade 110.”

The Feylis were a Kurdish tribe occupying the borderlands between Iran and Iraq who spoke a different dialect than most of their ethnicity. They were horribly persecuted under Saddam, and many were practicing Shias. A small but loyal armed band of Feylis was incorporated into the PMF’s integrated brigade structure.

Taghavi ran his finger back north to Tal Afar, an ancient city west of Mosul on the road to Syria. “Liwa al-Hussein, Brigade 53,” he said. “Our Shia Turkmen contingent.”

Al-Amerli looked curiously at the disposition of forces.

“We place these brigades under the Northern Operations Command,” Taghavi explained. “The Feylis advance north, Liwa al-Hussein advances east, rendezvousing near Lake Dukan.” He pointed to Iraq’s largest lake in Sulemaniyah province, then slid his finger a few inches northeast, landing on Mount Qandil. Much of the mountain sat on the Iraqi side of the border, directly across from Piranshahr on the Iranian side, making it an attractive refuge for Kurdish separatists.

They thought there was safety on the mountain.

“The brigades seize the roads to Mount Qandil,” he continued, “and hold there as a screening force for the Pasdaran. They block reinforcements from reaching the mountain and prevent any separatists from escaping. They’ll be trapped.”

“Both brigades would have to pass through miles of territory held by the KDP and the PUK,” al-Zaydi pointed out. “Why would the peshmerga ever allow them to push that far?”

“Because they belong there. They’re Kurds and Turkmen. They’re small enough to move undetected. This isn’t the Imam Khomeini Division marching on Erbil.”

Al-Zaydi still seemed skeptical.

“And the Turks?” Al-Amerli pointed on the map at Ninawa and Dohuk, where Turkey occupied two bases. “Will they interfere?”

“How large is that garrison?” Taghavi asked the room.

“Two thousand,” Mozaffari answered. “Roughly.”

“Turkey’s expeditionary force in the north serves nothing more than to deter the PKK and defend Turkmen around Tal Afar.”

Mozaffari leaned on the table. “We’ll do the Turks a favor by sending that mountain to hell. We’ll plow their bones into our fields.”

“How many are on the mountain?” al-Fayyad asked.

“Five hundred,” said General Zolghadr. “Not counting women and children, the lame and infirm.”

“We’re only hunting for one.” Taghavi stared at the map. And Haj Qasem means to purge a whole province to find him. “But Gorani is a small target in a vast wilderness.”

“Let the legions come forth, Abu Mahdi al-Mohandis,” al-Walai urged him.

“They are apostates and hypocrites,” Laith barked. “Let Barzani and his dogs protect that demon, Gorani. Daesh would have riven them were it not for our brigades. Let us liberate Kirkuk. Let us break them. Let them try us, even once, and Kurdistan will burn.”

• • •

It was after midnight when the Iranian delegation sped out Camp Husayn’s back gate into the empty desert toward Salum Air Base, seven miles northeast of the camp. The airfield was bombed by Coalition forces during the Gulf War and left abandoned until the Badr Organization claimed it, repaved the 10,000-foot runway and added modern support facilities with IRGC funding. Now the PMF used the base to launch drone operations east of the Tigris. Haider Mohammed Hatem accompanied Taghavi for the ride.

“The most honest answer I can give you, my friend, is, ‘I do not know.’ I have no better sense of this mess than you do,” Taghavi said impatiently.

“But surely you must have heard something?” Hatem insisted. “No one is closer to Haj Qasem than you. This is known. You are his favorite, Mohandis.”

“His daughter may disagree, but I’m pleased you think we’re close.” The conversation made Taghavi profusely uncomfortable, even if only Zamanian and al-Sabih were there to overhear it. It was unwise to speak carelessly about Qasem Shateri, and it verged on psychotic to speculate about what occurred in Paris. Hatem ought to know better.

“It’s inconceivable that this slipped past you. If Haj Qasem did this, he should claim it.”

“I’ll say this and nothing more, Haider,” Taghavi snapped, ensuring Hatem could sense his irritation. “I met Ibrahim al-Din once, decades ago. I never knew him, but I admired him, and I respected him. He is one of the greatest warriors the Islamic Revolution has seen—greater than you, that much is certain.”

The bluntness of Taghavi’s remark caught Hatem off guard.

“Hezbollah would have been better off if the party came under al-Din’s sober, military-minded leadership rather than the vanity and political hubris of Wissam Hamawi.” He shook his head. “But we would not have been better off. We are in the position we are in today because, while Hamawi mired Hezbollah in childish parliamentary games and used his men as cannon fodder even after Syria was obviously lost, we banded together effectively and liberated Iraq. That is why we control sixty percent of this country while Hezbollah must resort to isolationism and unilaterally disarm to remain politically viable in theirs.” Taghavi anxiously massaged the bridge of his nose. “I do not know the nature of Haj Qasem’s falling out with Hamawi, but I know him well enough to assure you that he won’t let it go unanswered. Would he try to take Hezbollah back? If he saw a strategy to do so, yes. Would he work with al-Din to overthrow Hamawi? They’re natural allies. Beyond that... what happened in Paris was reckless. I don’t see that as a winning strategy toward some coup against Hamawi.”

Sodium lamps illuminating the airfield’s main guard post came into view. “I apologize for my rudeness,” Taghavi offered after a moment.

“No offense was taken, sayyidi.” Hatem sounded deflated, like a scolded child.

“Even still,” he added, “I am not so reckless.”

The motorcade drove to the apron. A Harbin Y-12, a Chinese high-wing turboprop plane painted in the livery of the IRGC Aerospace Force, sat at the end of the runway, fueled for the ninety-minute flight to Tehran’s Mehrabad Airport. Just off the flight line, parked in hardened trapezoid-shaped shelters built by Yugoslavian contractors for Saddam’s air force, were Iranian Yasir and Ababil-3 UAVs reverse-engineered from American and South African designs.

Taghavi stepped out of the Lexus with Hatem and Zamanian. Mozaffari walked over from the other SUVs with Pakpour, Zolghadr, Ahmadian, and Hajisadeghi. His protective detail—Hadi, Ali, and al-Jaberi—set about stowing their luggage into the small cargo hold in the Y-12’s tail section.

“Send Haj Qasem my regards,” Hatem told him.

“Always. We’re meeting in the morning. He’ll be thrilled to hear what you and Ismail accomplished today. This mess in Paris has had Vaziri’s supporters on the streets for days. It’s got the chief commander’s staff occupied, but you’ll see preparations for the operation ramp up on our side of the border soon. Just get those brigades mobilized.”

“They’re leftists and anarchists. Little more than children,” Hatem dismissed. “What can they possibly do?”

“Don’t underestimate them,” Taghavi warned. “Plenty of yours were children, too... and look what they achieved.”

“The Basij will make quick work of the rioters in Tehran,” Zolghadr promised, “then we’ll turn our sights on Jamil Gorani and his filth.”

“When will you return?” Hatem asked.

“In a week or two.” Taghavi gestured to Mozaffari. “Baradar Shahroud will stay behind. He’ll coordinate with the Feylis and the Turkmen—and I want a tight leash on the Khazalis.”

“Laith is mad,” Hatem said soberly. “Qais protects him, but he’s unleashed true evil from Rusafa. Abu Iblis...” He spoke the name with venom. “We hear stories from Hawija. No Muslim deserves such horrors. Not even a Sunni. Not even a Sunni who sheltered Daesh.”

“I know,” Taghavi conceded. “When I return, I intend to settle everything.”

“Generals, Admiral, Hojjatoleslam,” Hatem turned to the others, “it was a pleasure to celebrate with you tonight.”

They thanked him.

Then Hatem offered Zamanian his hand. “My condolences for your loss, boy. You are forever in my prayers.”

Zamanian seemed genuinely touched. “Thank you, sayyidi. Bless you.”

“Safe travels, all.”

Hajisadeghi led the officers and Zamanian to the plane, but Taghavi held back. Mozaffari remained by his side.

Hatem embraced him. “I wish you good fortune, Abu Mahdi al-Mohandis.”

“And you, Haider.”

Taghavi and Mozaffari strolled across the tarmac as the Y-12’s twin engines churned the propellers alive. Once their whine was loud enough to mask his voice, Taghavi confided to the colonel, “Keep an eye on that one, too.”

Mozaffari clasped his hands behind his back. “I plan on it,” he replied. “The Khazalis are the dominant economic and political power in Saladin. They have a stranglehold on all trade between Samarra and Baghdad and they’ve controlled Sadr City since the occupation. Haider expects to be first among equals with us and the Khazalis are a threat to him. He only pretends to be appalled by ‘Abu Iblis’ because he wants Haj Qasem to cut Laith off at the knees.”

“Abu Iblis is a rabid dog. He’s blasphemous, his methods are barbaric, and yet,” Taghavi reasoned, “he is a loyal dog. Haj Qasem won’t put him down until he sees no use for him.”

“War between Badr and the Khazalis would serve no one.”

“No, and that’s why we’ll give them Kurds to murder instead of each other.”

They reached the plane.

“Don’t worry about anything here, baradar.”

“Never,” Taghavi smiled. “Colonel Shahroud Mozaffari remains in my stead.”

Taghavi turned and climbed the aft airstairs. Hadi hoisted them up behind him and sealed the door shut against the fuselage. The Y-12’s cabin was cramped, the ceiling so low that Taghavi had to hunch over slightly to avoid bumping his head. There were seventeen seats—two in each row on the starboard side and one on the port side—giving the nine of them plenty of room to spread out. Taghavi moved along the aisle toward the open cockpit door. The pilot and copilot looked up from their instruments and saluted as he poked his head inside.

“Good evening, General,” greeted the pilot.

“Evening, Major,” replied Taghavi. “You may depart when ready.”

“It’ll be a smooth flight home. Weather’s clear all the way to Tehran.”

“Yes, it’s a beautiful night, isn’t it?”

“Buckle in, General. We’ll take off shortly.”

His bodyguards, Ali and al-Jaberi, were seated starboard, closest to the cockpit; al-Sabih would stay behind at Camp Husayn to protect Mozaffari. General Pakpour and Admiral Ahmadian sat two rows back, locked in a heated discussion on Iran’s recent parliamentary elections and whether the Guardian Council approved too many “reformist” candidates. General Zolghadr sat across the aisle and struggled to get a word in between them. Hojjatoleslam Hajisadeghi was already asleep in the aftmost row, his turban cushioning his head against the starboard fuselage while the propellers drowned out his snores. Hadi occupied the opposite seat. Alone in the gulf between them, midway down the aisle to port, sat Captain Zamanian. Taghavi stepped aft to the hold and pulled a book from his suitcase, then buckled into the seat across from the captain.

“Baradar, would you like to sit with me?” he asked.

“Um, sure...” Zamanian shyly answered. “Only, uh, if you don’t mind, that is.”

Taghavi grinned. “Of course not, I’m inviting you.”

Zamanian hopped across the aisle and fumbled with his belt.

“Where were you last assigned?” he asked.

“The Joint Staff. Operations Division,” Zamanian answered.

“Ah, did you know General Zolghadr?”

“No... Well, I knew of him. But he didn’t know me.”

“What brought you to al-Qods?”

“I came up for promotion and was eligible for a transfer,” Zamanian said. “The Quds Force is legendary, even within the Pasdaran. The way I see it, you can’t fight the Islamic Revolution from a desk in Tehran.”

“No, you can’t, baradar,” he agreed. “No, you can’t.”

“I thank God for the opportunity every day.”

“Do you?”

“Always.”

Taghavi hesitated a moment. “May I ask you a personal question?”

Zamanian nodded.

“How are you, Vahid? Your family, as well. How are they?”

Zamanian turned and stared at the seatback in front of him. His eyes welled. “It... it’s hard,” he struggled. “It’s been six weeks, but we’re getting through a day at a time.”

“How old was he? Your son. Mohsen, right?”

“You know his name?” Zamanian asked happily.

Taghavi nodded humbly.

“Mohsen was three years old.”

“I’m so sorry. My wife and I never had a child, but I can’t begin to imagine—”

“Would you like to see a picture of him?”

“Very much.”

Zamanian took the wallet from his pocket and removed a photograph, worn and creased down the middle. “This is Mohsen,” he pointed, “and that’s my wife.” He offered it to him.

Taghavi studied the picture. A young family together on a blanket enjoying a summer picnic in a Tehran park. Mohsen, the smiling little boy in the middle, had already lost his hair to chemotherapy and looked pale and frail, even in the photograph.

It was heartbreaking, but Taghavi was glad he saw it.

He handed the photo back to Zamanian. “Take leave tomorrow. The whole day,” he said. “You should be with your wife.”

Zamanian sniffed and wiped his eyes. “Thank you.” He put the wallet back in his pocket. “You are very kind, baradar.”

Taghavi slid on reading glasses, took the book from his lap, and opened to a dog-eared page as the engines roared to full power. He could still feel Zamanian’s eyes on him.

“What are you reading?” the captain asked hesitantly.

Taghavi flipped back to the cover and showed him. “The Guns of August,” he said.

“You know English?”

“I do.” He removed his glasses. “My father was an oilfield worker—illiterate, barely able to read even the Quran—and in my youthful angst, I was determined to be nothing like him. I taught myself the summer before university. All the best chemical engineering textbooks are in English, anyhow.”

“Is it a novel?”

“No, it’s a history. In my study at home, I have hundreds of these. When I retire, I’ll have to buy a second house just for books!” Taghavi smiled. “My wife will loathe me.”

“What’s it about?”

“Well, it’s about the First World War, the ‘Great War,’” Taghavi explained. “Or, more specifically, it’s about the weeks before the war began. It’s about the great powers of Europe and their conflicting alliances and secret pacts. It’s about their scheming and strategizing against each other, all that intrigue and treachery.” He felt the brakes slip beneath him. The plane began rolling down the runway. “Then, on the twenty-eighth of June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to Austria-Hungary, was assassinated in Sarajevo by a Serbian nationalist, Gavrilo Princip. The tragic part is that the archduke wasn’t a monster at all, he was rather sympathetic to the Serbs.”

The plane glided into the air, driving them back against their seats.

“Within a month of his assassination, it all fell apart, and the entire world was at war. Twenty million people died because he died first.”

“That’s fascinating to me,” Zamanian replied, “how the world can work that way. How does something so terrible happen so quickly? How does it all spin out of control?”

Taghavi sighed. “That’s the nature of the universe, baradar. Things happen gradually, then all at once. Events that were once unimaginable suddenly become all too real, often before we understand the actions that made them real. None of the men who instigated history’s most disastrous wars could have comprehended the final toll when they began. When Cassius and Brutus conspired to murder Caesar, did they know it would tear Rome apart? When Napoleon retreated from Moscow at the outset of winter, did he expect most of his army to freeze and starve? When Hitler invaded Poland, did he think all of Europe would be leveled? Of course not. Would they have still done it if they had? That, to me, is a far more interesting question.”

The plane banked slightly to starboard and turned southeast, climbing.

“Men are stupid.”

Taghavi laughed. “Yes, they are.”

“I think most men just want to die gloriously in battle. They learn about the shahid, about the Five Martyrs and Imam Husayn, and they go to war expecting to die like them.”

Taghavi shook his head. “No man dies gloriously in battle. Even the bravest martyrs were terrified in that final moment before the end.”

“What becomes of them then?”

“They just die... same as us all.”

A searing white flash erupted behind Taghavi.

Then a thunderous roar.

Then the wind. Howling, frigid wind.

In the next instant, everything went dark. Thick fog filled the cabin. Alarms wailed in the cockpit—an incessant, shrill, ear-splitting squawk.

His stomach was thrust into his throat so suddenly he felt it might hurl out his mouth. He was falling, he realized. Rapidly. It was painful to breathe, as if the air was being sucked from his lungs.

And it was so cold.

The wind pulled at him so fiercely that he thought the belt around his waist was all that kept him from being launched from his seat and thrown across the cabin.

Taghavi impulsively reached out and slammed his arm across Zamanian’s chest, forcing him back into the seat. He didn’t know why. It made no sense, but he cared for Zamanian. He wanted to help, to protect him, even if it was useless. Zamanian’s whole body tensed, his eyes clenched shut, and his hands gripped the seat beneath him. And then Taghavi heard screaming somewhere ahead of him. Not mechanical screaming, not another alarm. This was different. It was a man screaming, crying in agonized horror, pleading for God. Who could possibly be screaming? he somehow wondered. It didn’t matter.

Oxygen masks fell loose from the ceiling.

He grabbed one with his free hand—he could barely see through the fog—and clutched it over his mouth. He gasped for air, pulling in as much as he could. Taghavi tried to get Zamanian’s attention, to show him the mask dangling inches in front of his face, but he wouldn’t open his goddamn eyes.

The screams were louder now, cursing God instead of pleading for Him. He hated it. He hated it so fucking much that the last thing he had to hear before he died was someone bawling like a goat with a knife stuck in its gut.

A computerized voice blared from the cockpit.

“Terrain! Terrain! Pull up! Terrain! Terrain!”

He wanted it to be over. Whatever came next—Paradise or hell or nothing—he didn’t care anymore.

“Terrain! Terrain! Pull up! Terrain! Terrain!”

And the screaming...

He just wanted it to end.

And then it did. Almost.

The wind stopped. The fuselage savagely lurched forward. He heard a deafening shriek. Suddenly, he felt weightless, like he was flying. Spinning! He was spinning. He lost all sense of up or down. Rocks and dirt pelted his face—he knew it was dirt because he could taste it. Then, the seat in front of him crashed into his nose, and everything went black.

Everything was quiet.

Until it wasn’t.

The screams brought him back. It sounded more like a moan than a cry now, like sobbing.

Taghavi slowly opened his eyes. He heard a pop, then a distant hiss, and the space around him filled with shafts of glowing red light for a moment or two, only to gently fade out, back to darkness.

There was a strange coolness in his left arm, and then he moved it, just an inch, and then he yelped. He dragged his arm into his lap and yelped some more. He looked down at it. The bone was broken above the wrist. His arm was oddly limp and swollen, the skin already hideously bruised.

He winced. A different pain shot through his skull.

Taghavi reached up with his right arm and touched his face. His nose was crooked, tingling and throbbing. Broken, too. He could feel the gash between his eyes. When he pulled his hand away, his fingers were slick with blood. He pressed his tongue against his front teeth. At least four were loose and an unpleasant metallic taste filled his mouth. He ran his other hand through his hair and found it caked with dirt.

It was cold, but not as cold as before. The fog was gone, and now the air was heavy with smoke and dust. He was sitting upright, still buckled into his seat. The fuselage around him was mangled, scraps of luggage strewn throughout the cabin. It must still be nighttime, he realized. Although if he’d been out for seconds, minutes, or even hours, he didn’t know. Where was he? Something happened to the plane. It— A crash! The plane had crashed, fallen from the sky. And he survived! But wait... Taghavi looked beside him. Zamanian was slumped over in his seat like a discarded doll. No, no, no, no. This wasn’t happening. This wasn’t real. He gasped for air, panicking, wishing he could only wake from this nightmare.

Again, the screams brought him back, focused him. He recognized it now. It was Pakpour’s sobs.

“Hossein!” he shouted. “Hossein, can you hear me!?”

“Help me! Please! Oh, Allah, help me!” Pakpour screamed.

“Do not move! I’m coming!” another voice shouted.

Taghavi didn’t recognize that voice, but it came from behind him and spoke Farsi like an Arab. Was it Hadi? “Hadi!” he cried. “Hadi, it’s Jamal! I’m here!”

“Don’t move,” Hadi answered.

Taghavi reached over and shook Zamanian. “Vahid, wake up.”

He didn’t respond.

Harsher this time. “Vahid!”

Nothing.

“Please!” Taghavi kicked his boot heel back hard against Zamanian’s shin. “Wake up!”

Zamanian woke. Suddenly. His eyes shot open, and he screamed at the top of his lungs. “Ow! Ow! OW!! OW!!!”

“What?” Taghavi croaked. “What is it?”

“My leg!!” Zamanian bawled. “It’s my leg! It hurts!”

Taghavi glanced over at him and shuddered. The jagged tip of his right femur pierced his pant leg, the fabric around it soaked black with blood.

“Hadi, we need help!” he shouted behind him, then hurriedly unbuckled his seat belt with his good arm. He wrestled himself free and clumsily climbed over Zamanian, who screeched in agony as Taghavi’s boot brushed against his leg, then slipped and fell flat on his face in the aisle, cursing as he went down. Taghavi grabbed a seat and pulled himself back up, banging his head against the ceiling, and looked toward the cockpit—or rather, where the cockpit had been.

The plane rolled in the crash. Taghavi had felt it. Now the forward section of the fuselage was crushed like an aluminum can. The two pilots, Ali, al-Jaberi, and Zolghadr—he could only see gory ropes of flesh tangled amid the twisted metal, like meat stuck in a grinder. Taghavi staggered forward, his knees wavering beneath him.

He understood why Pakpour kept screaming.

Ahmadian’s head had been dashed against the fuselage. Pakpour was trapped beside his corpse, pinned into his seat by the wreckage, covered in brain and bits of skull.

“I sent up a flare,” Hadi said. “Minutes ago.”

Taghavi turned and found Hadi standing in the aisle, his hand tightly gripping a Browning Hi-Power sidearm. “What happened?” he muttered.

“A bomb.” Hadi pointed to a five-foot breach in the fuselage’s tail section, gutting the cargo hold. “We went down in an oilfield. I think we made it over the border, but I can’t get reception.” He noticed Taghavi staring at the empty seat where Hajisadeghi had been. “Gone. Sucked out after the blast. I saw it.” He shook his head. “I barely held on.”

“Why the gun?”

Zamanian groaned.

“We have to get them out.” Hadi pushed past Taghavi and crouched beside Zamanian. He took out a pocketknife and began sawing through the seatbelt. “Help me.”

Taghavi limped over, grabbed one of Zamanian’s arms while Hadi grabbed the other, but he wouldn’t budge.

“No! I can’t! I CAN’T!” he screamed.

“We have to get a tourniquet around his leg and stop the bleeding,” Hadi barked, then looked to Taghavi. “Again.”

Again, they tried to hoist him up, but Zamanian couldn’t.

“Please! Put me down! Ow! You’re hurting me!”

“Fuck!” Hadi backed off. “Stay with them.”

“Where are you going?”

“To signal for help. Some worker’s bound to see the flare.” Hadi rushed aft and climbed through the breach in the fuselage.

Taghavi sat down beside Zamanian. After a few minutes, Pakpour thankfully stopped screaming and Zamanian went faint. Then he heard Hadi yell outside.

“Here!”

Taghavi came to his feet and staggered through the breach.

The pilot had brought them down in a desolate field of rocks. The initial impact sheared off the wings and threw the fuselage forward, tumbling uncontrollably until coming to rest as the mangled wreck before him. In the moonlight, Taghavi could see the surrounding wasteland—miles of rocking oil derricks and gas flares blooming in the distance. He wondered for a moment if he was actually dead and in hell.

Then Hadi cried out, “We’re here!”

Headlights gained on them at high speed. Hadi kept waving his arms until they came close enough to see him. There were three SUVs, Isuzu Troopers marked with the logo of the Iranian Central Oil Fields Company.

Taghavi felt relieved, even hopeful.

The SUVs stopped. Men stepped out.

Hadi went to speak to them, but then something startled him. He recoiled, swiftly pulled up his Browning, and squeezed the trigger twice.

One of the men fell, but others rattled back a quick burst of gunfire.

Hadi staggered backward, dropped, and was still.

Then they began walking, patiently, toward Taghavi.

He shuddered, his entire body trembling with fear, and hobbled as fast as he could back inside the plane, tripping over the fuselage. What could he do? He had no weapon. Everyone else was dead or dying. He crawled up the aisle, ignoring the pain pulsing through his broken arm, and crammed between two rows of seats. “Vahid, you have to play dead,” he whispered. “Don’t move. Don’t make a sound.”

Zamanian whimpered.

Taghavi slumped over and squeezed his eyes shut.

It was unbearable not to breathe. His heart raced.

He heard footsteps climbing into the wreckage, softly, moving closer to him, and stopped.

“Hello,” he heard a woman’s voice—a girl’s, even—say pleasantly, then put a bullet in his gut.

Taghavi gasped in shock, throwing his eyes wide open. He pressed his hand against his abdomen as tight pressure surged through his stomach and intestines. His legs squirmed.

Zamanian and Pakpour screeched at the shot.

He found three young men and a woman standing inside the plane. They looked like poor Iraqis—Kurds, Arabs, or Yazidis—and wore faded khaki coveralls used by oilfield workers under combat webbing and magazine pouches. The men blithely toted Kalashnikovs. The woman held a Glock 19 on him.

They said nothing.

Then, a hulking, much darker figure ducked into the breach and climbed through the fuselage. The man was huge, hunched over at the shoulders, and pressed his massive arms against the ceiling, his stench flooding the cabin. Hung from his belt was a fourteen-inch curved dagger with an ivory hilt sheathed in a scabbard of stitched golden velvet. Taghavi saw the glimmering eyes, the coarse, unruly mane, and the beard tied into three prongs like a pitchfork. Only the man’s hair wasn’t jet-black anymore. It was gray and filthy and brittle. It was Jamil Gorani, the Dark Lion of Kurdistan, tempered by war and grief into a vengeful shade teeming with malice.

Taghavi tried to curse at him but only coughed up blood.

“Ten minutes,” one of the men alerted.

Gorani gazed down at Taghavi, appraising him like a cockroach, then turned stiffly toward Zamanian. “Get this one out,” he ordered, his deep voice rippling through the cabin.

Two men grabbed Zamanian under his armpits, heaved him over the seats, and let him flop onto the aisle. Gorani’s gray, cracked lips tightened at the sight of the shattered, bloodied bone jutting through the young captain’s pant leg. “Search,” he said over Zamanian’s howls.

“Leave him alone,” Taghavi croaked, but they ignored him.

One of the men removed Zamanian’s wallet and passed it to Gorani. He opened the bifold as Pakpour, still pinned in his seat, moaned like a wounded animal. Gorani swung his body around, pointed at Pakpour, and asked brusquely, “Why is this one making noise?”

Another man sauntered up the aisle, placed the muzzle of his Kalashnikov against Pakpour’s head, and fired, obliterating Pakpour’s skull with a sharp clap that rang in Taghavi’s ears.

Gorani leisurely thumbed through the wallet’s contents. Then the photograph stopped him cold. His gaze drifted down upon Zamanian like he’d found something unexpected, something intriguing and worthy of further inspection—something relatable. “This one comes,” he decreed.

One man took Zamanian under the armpits again and dragged him down the aisle like a rolled carpet. Zamanian wailed madly about his leg, delirious and pleading for them to stop. A second man grabbed Zamanian by the ankles, hoisted him up, and the two carried him from the fuselage. The third man followed them out. Taghavi stopped hearing Zamanian’s screams after that.

Then there was only him, the woman, and Gorani, alone.

The woman backed away.

Gorani unsheathed the dagger on his belt and crouched beside Taghavi, his aging joints weary at the close of a full day’s work. “Salam, Abu Mahdi al-Mohandis,” he greeted, gently waving the blade inches over Taghavi’s face. He slid the dagger between the buttons of Taghavi’s blood-soaked shirt and sliced it open in one smooth motion, then gently flicked the fabric apart with the blade’s tip, exposing Taghavi’s chest and abdomen and the fresh, weeping bullet wound in his stomach.

Taghavi coughed. Everything was numb.

Then Gorani looked at him, looked at the dagger, looked at him again, then sighed with a deep sadness that held in the air for a moment and muttered, “Tonight, you walk amidst the ruins.”

Taghavi groaned when the fourteen inches of Damascus steel thrust into the fleshy space below his diaphragm. It was a different sort of pain from any he knew. Not sharp and throbbing, but dull and cold and all-enveloping, like an alien organism rooting through his insides, like a malignant itch just out of reach under the skin. The shock made him feel dizzy and nauseous. Gorani sawed horizontally, bypassing his ribcage and sternum, severing arteries and ligaments. Taghavi felt blood filling his lungs, warm and thick, and when Gorani reached deep into his chest cavity and pulled out his heart, he might have screamed, but it didn’t matter. He watched his own still-beating heart. Taghavi always wanted to be a martyr, even though now the thought terrified him.

He just wanted it to end...

And then, same as all the others, it did.

To be published by H-Hour Productions, LLC. Copyright © 2024 Matthew Fulton. All rights reserved.

Photo by John Moore/Getty Images

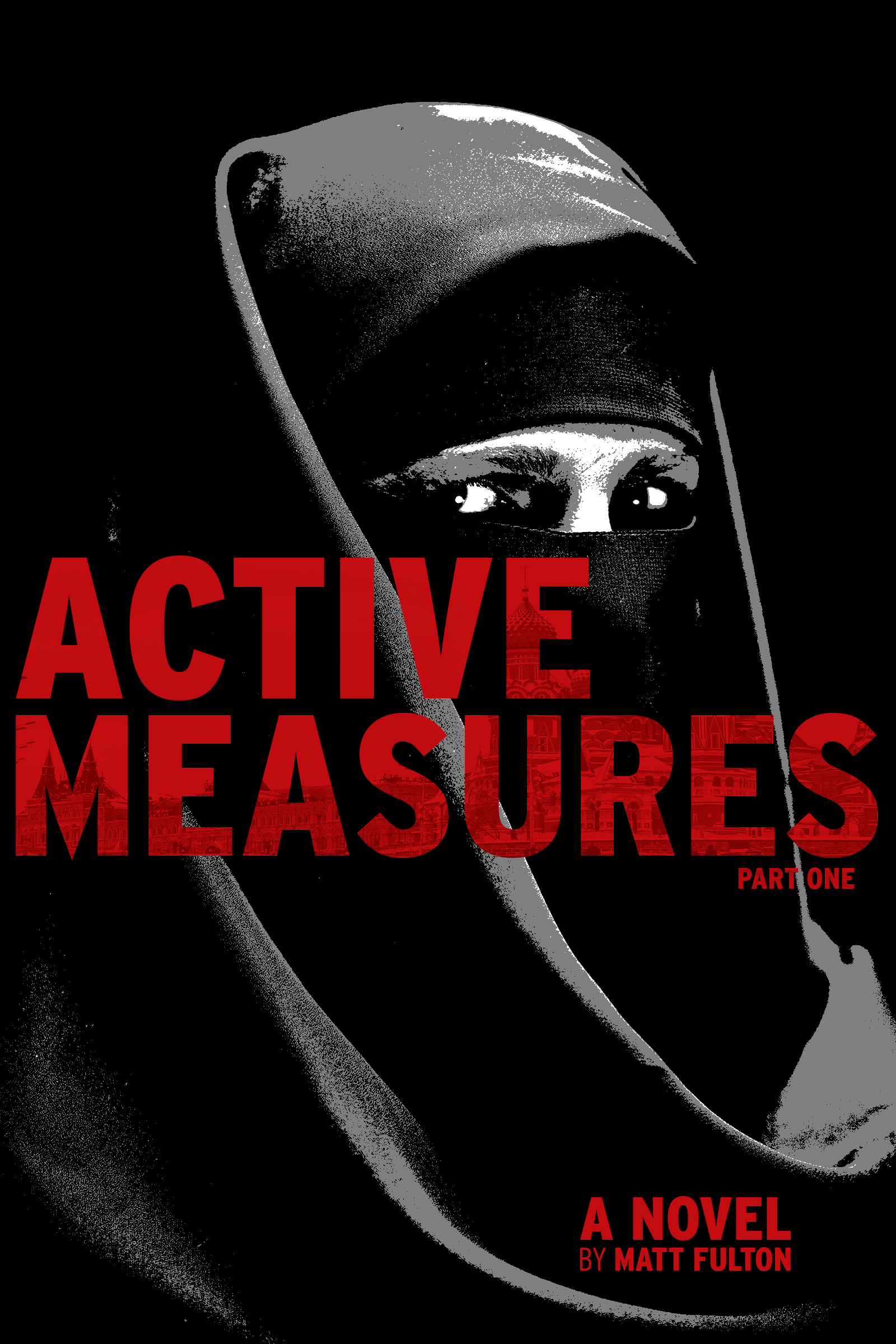

See how it all begins...

Discover the novel readers call one of the most ambitious geopolitical thrillers in decades.

"If The Lord of the Rings is epic fantasy, then it would be fair to say that Matt Fulton writes 'epic espionage.' Active Measures is in a class by itself!" — Andrew Warren, best-selling author of the Thomas Caine series

"Timely, gripping, and unbelievably authentic..." — Stephen England, best-selling author of the Shadow Warriors series

"A sophisticated and masterfully written tale about the dangers of loose nukes, terrorism, and espionage." — Best Thrillers

Active Measures: Part I is available on Amazon

Want to be the first to know when more previews are released?